On September 2, 1942, a plane on a search and rescue mission off the coast of Iceland plunged into the sea, killing the pilot and 39-year-old passenger. The passenger was Eric Ravilious, whose last letter to his wife three days ago praised the deep shadows and leaf-like cracks of the subarctic landscape. He was one of 300 artists hired by the War Artists Advisory Committee to cover World War II and was the first artist to die on active duty.

Back at their damp Essex farmhouse home, she and their three young children, his wife, Deza Garwood, struggling: She recently had surgery for breast cancer that would kill her nine years later. Illness and the stress of family life took a toll on her successful career as an artist. But every night, after putting the kids to bed, she sat down and typed out her autobiography.

It was written directly to her future readers: “I hope you may be one of my descendants,” she wrote, “but I have only three children, and as I write, a German plane is in my head Circling up and taking pictures of the damage. Yesterday’s attackers did it, reminding me that our survival is uncertain.”

Ravilious’s reputation as an artist of any value barely exists. By the time of his death, a huge mural at Morley College in Waterloo had been blown up, some of his war paintings had been censored, and dozens more had sunk into the sea on their way to a promotional art exhibition in South America. For more than 30 years, most of his surviving work is forgotten under a bed in the house he and Garwood once shared with artist Edward Bawden, leaving only Wedgwood. Commissioned mass production of playful letter cups and a woodcut print. The gentleman in top hat who has been on the cover of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack for years.

But a new movie, Eric Ravilious: Attracted by war, straight to the point, attracted an impressive array of advocates – from Grayson Perry to Alan Bennett – proving that he was one of the great British artists whose prints broke new technical realms, while His watercolors brought Turner’s tradition into the 20th century. The film is the passion project of its writer and director, Maggie Kimmonswho started working on it 15 years ago, but was insisted that no one had heard of Ravilious’ backers repeatedly objected.

Kinmonth’s last film was a 2017 documentary about a revolutionary artist in Russia, but when the pandemic hit, she realized she had to look closer to home, so returned to the revolution she’d already recorded with surviving Interview clips of members of the organization. Greedy family. “They call art the tumbleweed of television,” she laughs, “but fortunately, film and art go together well.”

Her perseverance paid off. A circle of “friends” stepped in to help with financing, and more than 70 movie theaters have signed on to show a film that is both a comprehensive account of a passionate but unconventional marriage and a persuasive curatorial journey. Its quiet surfaces are never what they seem.

Nature author Robert Macfarlane, featured in his bestselling book Ravilious old way, pointing to the way the artist will use barbed wire to outline an idyllic watercolor of the southern English countryside. “I think Ravilous is as deadly an example of a Briton as a climber George Mallory and poet Edward Thomas: They didn’t have to go to war or climb Mount Everest, they all died in their 30s and lived the life they dreamed of as children. It’s an old and deadly love of the landscape. As a result, Macfarlane said, “Thomas and Ravilious were both considered quaint countryists, when in reality they were not – they were modernists”.

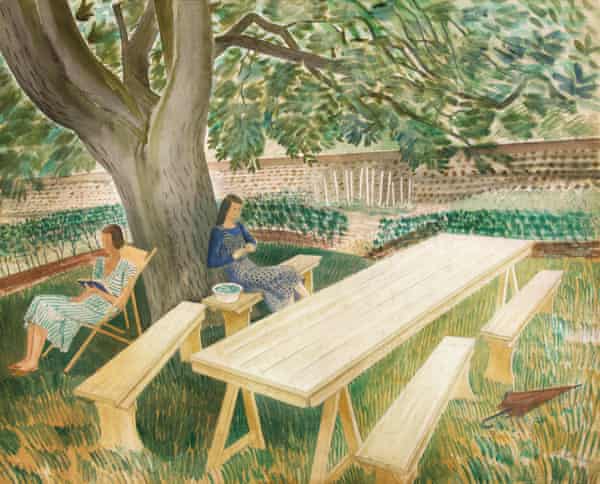

Wiltshire landscape painting is one of the artist’s most famous works A lively red van Approaching the intersection of a road leading to an ominous future (it was created for artists opposed to fascism). A domestic scene with an empty outdoor coffee table under an umbrella is named Tea at Furlongs, but could be called Munich 1938, reflected in the film by Alan Bennett, citing WH Auden’s prewar poem Witness: “Something will fall like rain/It will not be a flower.” Most notably, in a letter to Garwood describing his shock at witnessing a young pilot drown during a military exercise, The letter is juxtaposed in the film with a painting of a biplane gently swinging over the sea seen through a window.

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei admits he knew nothing about Ravilious until Kinmonth approached him for his installation bomb history at the Imperial War Museum. “I was curious to see how a war artist works, so I accepted the invitation to work on the project,” he said. He was surprised by what he found. “He had such a calm look and such a naive, almost naive look. I was struck by the authenticity, attention to detail and humanitarianism of his artwork about war. He was able to observe and Expression. While a lot of his work is watercolour and seemingly understated, it is profound, rigorous and detailed. I think Ravilious is one of the best artists in the UK.”

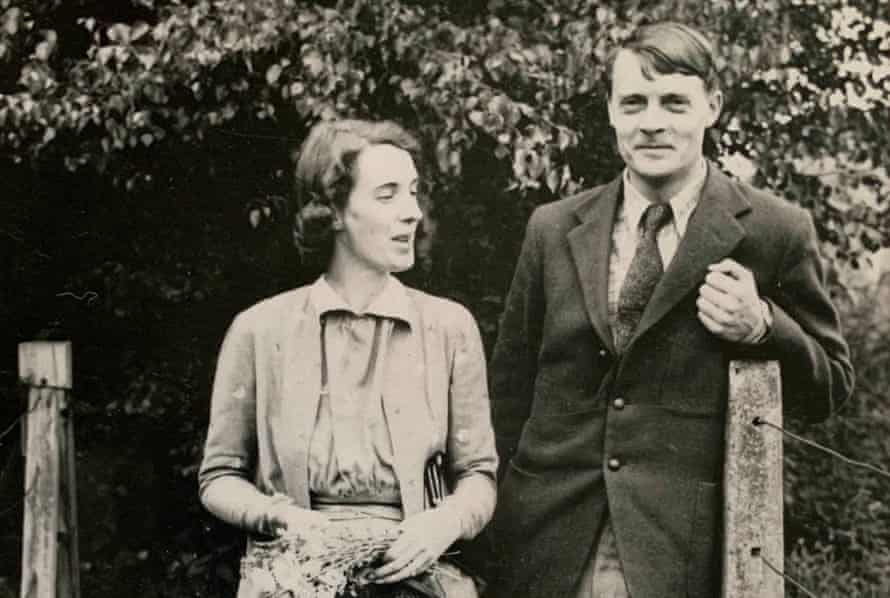

The film begins and ends with a never-heard distress signal from a doomed plane, before returning to Ravellis’ childhood in the Sussex countryside, where he happily painted ordinary objects—a Take the brush and bucket, his father’s collar and tie, as well as the plane over the Chalk Mountains. He went on to receive a scholarship to the Royal College of Art and, while teaching at Eastbourne College of Art, met the Colonel’s daughter Garwood, who was studying woodblock print, and whose parents snobbishly objected to their relationship.

The story is semi-dramatic, and the task of voicing Garwood fell to Tamsin Gregg, whom Kimmons approached after seeing her play at the Hampstead Theatre. Greig was also not familiar with Ravilious’s work. “I was drawn to this film because it really is a love story between two people with similar passions, but there is a cost to the collaboration between two artists, and it’s something someone has to bear,” she said. . “They were trying to combine the wildness of creativity, but also living within the constraints of the social system.”

In her autobiography, Long Live Great Badfield, Garwood is open about the impact of two things Eric has publicly pursued on her, starting with her pregnancy with the first of their three children. Her narrative is painful, but never self-pity. “I love the deep feel of writing on a very thin cuticle,” Greg said. “I found Maggie’s storytelling to be very tender and elegiac.”

Part of the story is told by Ravilious and Garwood’s daughter Anne, who was a baby when her father was killed (in her autobiography, Garwood recalls trying to pick her up and wave goodbye) and she was only 10 age. Mother also died. As Kinmonth points out, if she hadn’t made public the couple’s private letters and all the correspondence between her father and his two lovers, the film wouldn’t be as layered as she inherited after their deaths.

Despite the turmoil and injustice in their relationship, there is a balance between Ravilious and Garwood as artists, which is made clear in both of their photos. Both are third-class train cars that travel through the countryside. But while Ravilious’s watercolor carriage is empty, with a white horse carved into the hillside in the distance, Garwood’s woodcut is packed with passengers.

Sadly, the couple’s granddaughter Ella Ravilious, now a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, was tasked with reading passages that Garwood left her book to posterity, if the book survived. “If you are not of my descendant,” continues a passage outside the film, “then I only ask that you love this country as much as I do, and when you walk into a room, look closely at its pictures and its furniture, and sympathize with the painter and craftsmen.” It may be a great man’s story, but it’s a woman’s story.