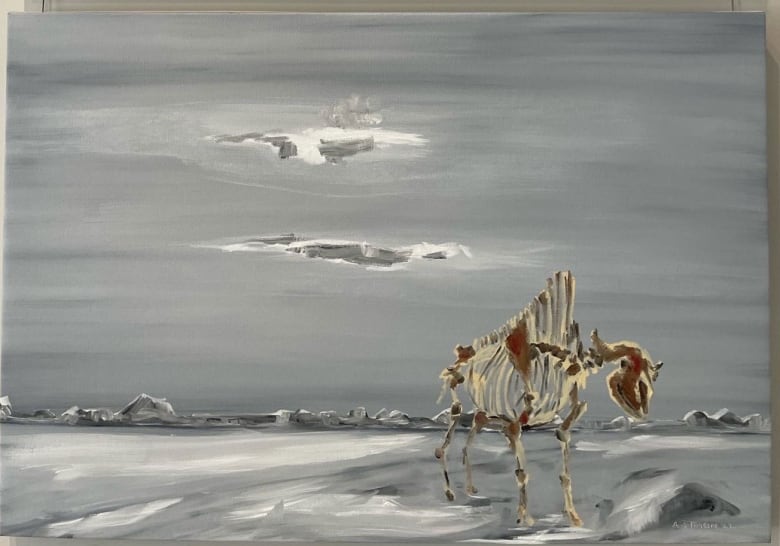

A solitary bison walks across a snow-covered prairie plain covered in rich reds and dark browns, the only sign of life in an otherwise barren landscape.

Variations of the image appear over and over again in the first European solo exhibition of Aboriginal Alberta artist Adrian Stimson, which opens in London, England, on May 16.

Stimson said he wanted his collection, titled Checklist Buffalo: Bison Dreamwill create a space for people to have a conversation with Aboriginal people about Canada’s dark history.

The title of the exhibition is a tribute to “mandate of heaven,” the 19th-century cultural belief that North American settlers were destined to colonize the continent.

“As human beings, we all have to live in harmony. But that doesn’t mean we should forget what happened, because when we forget what happened…it keeps happening,” said Stimson, 58, a member Representative of the Siksika Aboriginal Nation, who spoke with CBC on opening night.

Among the 36 paintings created exclusively for the exhibition, Stimson reimagines bison in a variety of scenarios: sharing a canvas with a nuclear explosion; fencing with pipes; and a calf jumping playfully in the air with an oil rig in the background.

Art buff Adam Heaton visited the exhibition on opening night and didn’t forget this centuries-old icon of the savannah roaming alongside modern objects like airplanes.

“There’s a theme of past, present and future here, but you’re not quite sure what the future is, and there’s an inherent tension in it,” Heaton said.

‘It’s something different’

Senior director Spencer Ewen said the Stimson collection, housed in a small gallery by art consultancy and appraisal group Gurr Johns, was a welcome addition to the Old Masters that adorned the space’s walls a week earlier. Genre changes.

“It’s something different,” Ewen said, “but equally valid and equally relevant.”

He reflects on the importance of Aboriginal voices forging a platform on the historic ‘fortress of traditional arts’ Pall Mall, which was the centre of London’s fine arts scene in the early 19th century.

Once home to the Royal Academy, the National Gallery and the Christie’s auction house, the artists permitted to develop and display their work here are white European males.

Not only is Stimson native, but he has a gender-bending alter ego named Buffalo Boy, who provides a strong contrast.

Stimson’s European premiere was attended by Jonathan Sauvé, head of public diplomacy at the Canadian High Commission in the UK, who thanked Stimson for bringing his art to the UK.

“Canada has a lot of work to do…but we strongly believe that arts and culture may be the best way to foster reconciliation and expression among Indigenous peoples,” Sovey said.

Stimson, whose Blackfoot name is Little Brown Boy, started painting in 1999 after resigning as an Aboriginal tribal councillor. He considers himself an interdisciplinary artist whose sculptures, photography and performances have been exhibited in Canada and internationally.

This isn’t the first time Stimson’s reimagining of the bison has caught the attention of the London art world. In 2016, two of his paintings were collected by the British Museum for the collection of Blackfoot.

The role of bison

Stimson said the historical and cultural significance of bison to Aboriginal peoples is a major reason why bison is so prominent in his archive.

The bison was a source of food and clothing, and a fixture of the Siksika spirit, which, among other purposes, was almost entirely wiped out by the fur trade, as detailed in George Colpitts’ 2014 book The Pemmican Empire: Food, Trade, and the Last Bison Hunt on the North American Plains, 1780-1882.

“Every time I paint a bison, it’s a memory of those who were slaughtered,” Stimson said.

“At the moment of the slaughter, I believe that that energy, those particles, was released into the universe. And I believe that it is still in and around us. So as an artist, I get the joy and the privilege of being able to do it. Go into that ether, grab that energy, bring it into myself, create works.”

Siksika Nation’s relationship with the royal family

At the exhibition opening, he said, Stimson welcomed attendees with black feet and wore his traditional headgear, bringing his ancestors and descendants into the room.

He added that donning his kingship also reaffirmed the special relationship between the Sikhsika people and the royal family, which was cemented in legislation through a treaty signed in 1877 that established a land for the tribe, promising An annual fee is paid to the queen and secures the right to continue hunting and trapping in exchange for Sikhsikas relinquishing rights to their traditional territories.

Stimson insisted that this “state-to-state relationship” would remain strong as long as “the sun is shining, the grass is growing, and the rivers are flowing.”

Checklist Buffalo: Bison Dream The same week it opened, other members of the Stimson Nation were heading to a museum in Exeter, southwest England, to return several items belonging to Crowfoot, the late 19th-century leader of the Blackfoot.

Stimson himself was invited to participate. As the past president of the Aboriginal Alliance Cultural Education Center, Stimson said he “reposted a lot of legislation on the repatriation of historical artefacts”.

In bringing the herd “to London”, the bison was once again a means of survival, evoking painful memories of colonization and educating the world about the resilience of his people, the artist said.