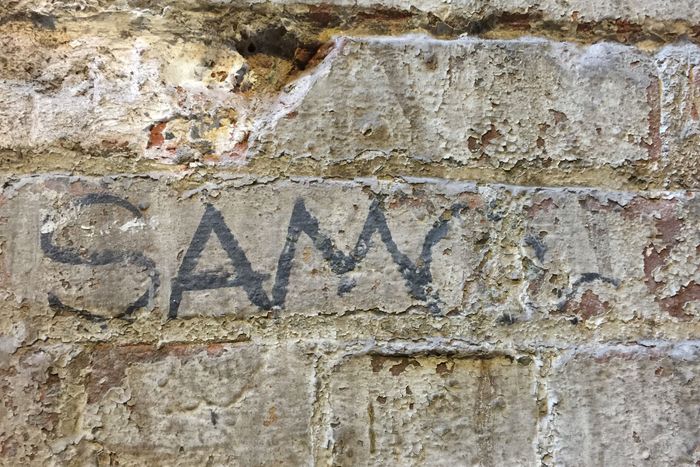

Documentary photographer Dona McAdams discovered the SAMO label around 1979 in an elevator shaft at 53-55 South 11th Street, a factory where she once owned an attic.

Photo: Donna Ann McAdams

South 11th Street consists of two short blocks between Kent Street and Berry Street, right at the tip of Hasidic Williamsburg. “When I moved in, it was almost in ruins,” Jim Fleming said of the 53-55-year-old six-story factory turned artist’s loft, who has been with his wife Levan since 1982 Jones lives here. Today, the building is ordinary mid-range real estate; the once sprawling loft has mostly been remodeled, One- and two-bedroom apartments rent for about $3,000 per month. The loading dock leading to the freight elevator, which once kept residents working around the clock, is now clogged with cinders, but you can still see its outlines through the paint.

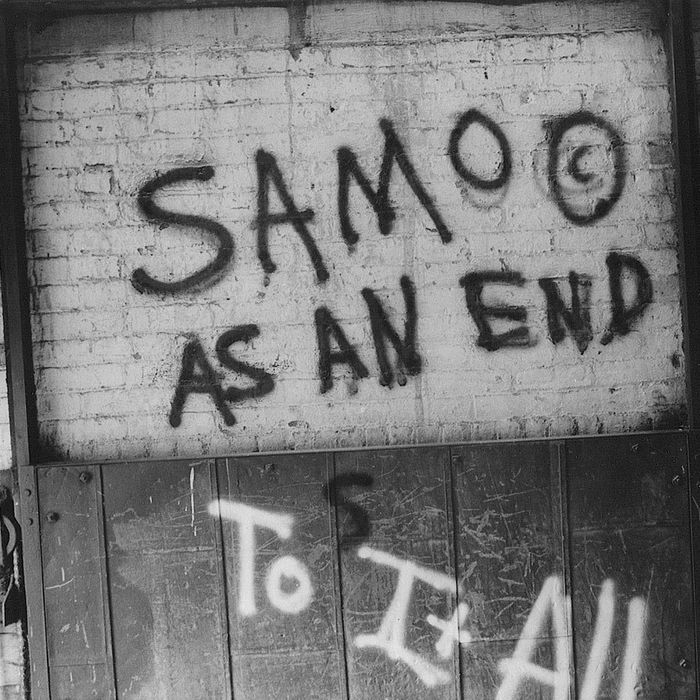

What you don’t see, Fleming and Jones say, are the remnants of their architecture’s brush with New York art history. In the late 1970s, cryptic messages began to appear on buildings around the city: “SAMO© AS END 2 THE NEON FANTASY CALLED ‘LIFE'” or “SAMO© AS AN END TO BOOSH-WAH”. December 1978, this Village Voice It was revealed that Jean-Michel Basquiat and a group of friends and collaborators were behind the graffiti. (The newspaper called them “The New Wave of Magical Marks Jeremiah.”) The labels eventually reached 53-55, where they were scribbled between landings. The writing is small, and the full label takes up the length and height of a brick. They are gadgets, stories that have been passed down among the inhabitants over the years. Legend has it that Basquiat came to the building with Andy Warhol, “but all of this stuff could be apocryphal,” Jones said.

Artists and Archivists Henry Flintwho created first file SAMO, who doodled and photographed the building 25 years ago, had told Fleming that he “lived in the Sistine Chapel in Basquiat by chance”. They didn’t last. After the building was sold in 2004, a renovation transformed industrial elevators into smaller passenger elevators and stairwells, burying every remaining SAMO label forever in layers of paint and drywall. “When they install new elevators, it’s like, ‘Oh, they’re so stupid!'” Jones said.

When Jim Fleming and Lewanne Jones moved into their Williamsburg loft in 1982, they noticed a small SAMO label on the wall of their freight elevator shaft. Jones photographed the label around 1990, before developers painted it and installed a passenger elevator around 2015.

Photo: Lewan Jones

Before the renovation, evidence of past occupants was everywhere: a box of chopped $1 bills in the basement, Fleming, Publisher, used to pack his books and spindle bucket. The SAMO label gets the most attention.In the same elevator shaft there used to be a larger elevator with letters at least two feet high, “SAMO© is the end of everything.” Documentary photographer Donna McAdamsShe, who lived in the building in the late 1970s, remembers finding graffiti while traveling. “It didn’t seem like a big deal at the time because he hadn’t been found,” she said. At some point between McAdams’ move out in 1979 and Fleming and Jones’ arrival in 1982, those large letters were painted out and smaller labels appeared.

As neighborhoods around 53-55 develop, new construction rising along the waterfront narrows the building’s river views. In 2004, the complex, including 53-55, was sold to Dov Land LLC, and the long-time tenants found themselves at an impasse with the new landlord. (“Rent values have risen through changes in neighborhoods and inflation and other market forces,” a lawyer for Dov Land told New York era year 2006. “Landlords, like any landlord who owns a building, want to maximize rental income.”) Buyouts and other tactics to drive tenants away worked—and many artists left. The building was carved into two addresses, 53–55 and 65 South 11th Street, and the freight elevators that once served the entire building became passenger elevators for only 65 people. This is the end of the SAMO label, residents say. “People came to see the graffiti,” said Jones, the archival filmmaker, but the landlord didn’t care. (The building’s property manager did not respond to a request for comment about the graffiti cover-up.)

This is more or less the case in New York. Sometimes the loss is small; others find it impossible to miss.After the demolition by the developer 5 o’clock — An abandoned factory complex in Long Island City that has become a graffiti mecca — build luxury rental21 artists Won a settlement of nearly $7 million work for them. There is now a set of commissioned murals on the side of the building facing the 7 train tracks that attempt to replicate the authenticity of the once sublime art-covered structure of 5 Pointz, but ultimately fail.

Every now and then, some famous murals are saved from the wrecking ball, such as Keith Haring’s Graffiti on the wall of the Boys Club of New York in 1987Other times, they are eaten by the same force in different ways: a Harlem mural cut from the Upper West Side Youth Center was Auctioned for $3.9 million in 2019.

In addition to the Basquiat connection, SAMO labels at 53–55 and 65 South 11th Street are a reminder that the once-1,000-person party will go on until 6 a.m. in an abandoned warehouse on the East River, while artists and their neighbors, mostly working-class Immigrants from Puerto Rico and Poland, can actually afford to live in Williamsburg and adjacent Green Point. Today’s buildings don’t look like they used to. There are about nine refurbished units per floor, the same space that once housed two artist lofts, such as the one shared by Fleming and Jones, which still has its original wooden floors and exposed beams.

At first, the couple was indifferent to the graffiti, but as the years passed, the labels started to become special. Whenever new people came in, the former elevator operator proudly pointed them out, and as word spread that there was a Basquiat in the building, people started coming just to read the labels.you don’t have to pay $35 (or $65 to skip the line) See Basquiat; it’s art history in the wild. “In the past, these things were just a dime a dozen,” Jones said. “Honestly, you know, you see it all over the place.”