Tonhe is fascinating Cornelia Parker Investigation It’s been open at Tate Britain for about 20 years now, but better late than never. At 65, with her poetic and highly original imagination, Parker Enough masterpieces have been produced to fill a full-scale retrospective, or even spill over into the surrounding galleries.

The show opens with a radiant thirty pieces of silver, hanging spotlights in the dark. Thirty flat sets, each made from 30 pieces of Edwardian silver, each teapot, plate and cake fork now resemble some nostalgic Christmas pudding charm. Everything hangs on a thread, inches from the ground, a bright symbol of free-falling Downton Abbey.

Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View – The same prototype of the potting shed, specially blown to pieces by the British army – appeared midway, its fragmented galaxy forever frozen in mid-air. An old Thermos, a Bakelite clock, a handed down stroller, broken rain boots: in its never-ending explosion, everything smells of England, it’s gone forever, but never quite. The entire spectacular period work, repeated in the shadows wafting on the walls, suggests explosions of all kinds: astral, accidental, artificial. No one looking at it now, along with shards of washing machines and windows, would not have thought of Russia bombing Mariupol.

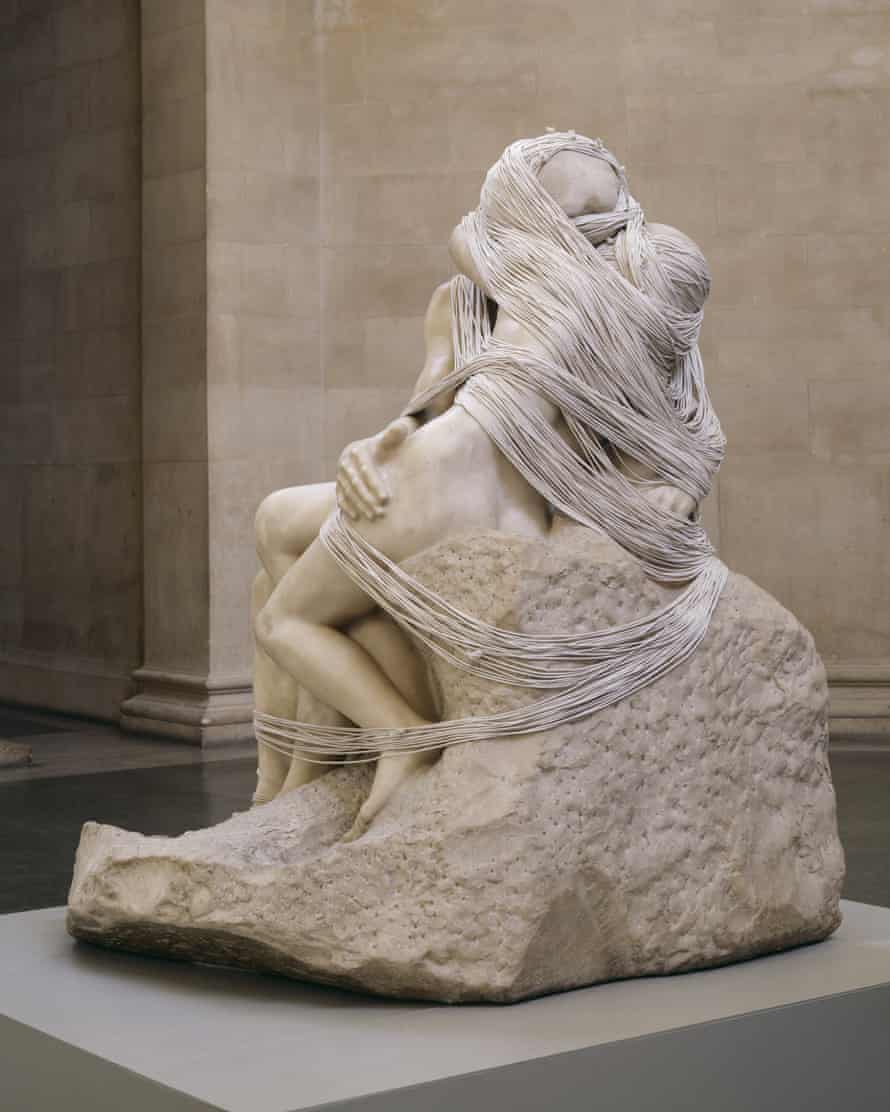

Parker’s artwork is scattered throughout the museum. A handkerchief tarnished by the spurs of Charles I, after her painstaking cleaning, developed the strangest stain, somewhere between portrait and history. An old canvas lining of Turner’s paintings, mounted on the walls of the Turner Gallery, now looks like a creepy Roscos.You’ll be greeted by Parker’s wonderful performance of Rodin on arrival at the Manton foyer the kiss Use a mile of rope.

Lovers’ faces now covered, like those in Magritte’s fatal painting of a couple trying to kiss through the cloth, their marble hugs became very ambiguous. This blind love, an allusion to Dante’s Paul and Francesca, is destined to never meet (Rodin’s profile), or do you see a couple fatally bonded?

Parker’s art is an art of translation, transformation, redemption. She created something from nothing, from old to new; poetry that turned reluctant material into objects.

A bullet melted and spun into thin thread is used to create the most delicate drawings, reminiscent of the American artist’s crosshairs and graphite abstractions Agnes MartinCracks between the paving slabs at Bunhill Fields in London, where Daniel Defoe and William Blake are buried, were cast in bronze tracery and hung above the ground like a The dragon head of an ancient tomb, or the grid of a minimalist sculpture. traces left by workers Pointing to the walls of Pentonville Prison, Parker intently notices and shoots what looks like a monochromatic abstraction Robert Motherwell.

Parker’s own conditions for what she did to her were incomparable. Sculpture negative, for example, does exactly what it sounds like.The remnants collected by the silversmith from his hand-carved inscriptions became shiny little pile, instantly evoking unspoken words. Cutting tracks into black lacquer pans at Abbey Road Studios produces fine lacquer coils that Parker winds into a vibrating sound cloud.

Some of the exhibits amount to an earth-shattering crime museum. The killer’s gun became a pile of rust-red dust: its own deadly wreckage. The artist took pictures of the fiery clouds using a camera that once belonged to Auschwitz commander Rudolph Höss. An Oliver Twist doll, with one eye closed and the other open, and a mouth that’s a comical cake hole, has been cut in half by the guillotine used to behead Marie Antoinette, so to speak.

Seeing a Holocaust Nazi through the same lens definitely made more sense to Parker than it did to us. My feeling is that the resulting images will never have exactly the same meaning. Meaning is central to this art of metaphor, evocation and suggestion. A series of Rorschach prints were made using rattlesnake venom and its antidote mixed with black and white ink. Parker commissioned local farmers and pharmacists to supply the substances during his residency in Texas. But you need to know this for fingerprints to hold any potency, which is tantamount to the power that kills or saves you.

Parker always leaves room for debate; there is no despotism here. The hand-sewn backs of old button cards reveal the fruits of ancient women’s labor, sketching beautiful abstract pictures; but they are photographs, not the actual artifacts themselves. Hasn’t the human touch been wiped out? The blackboards where schoolchildren chalk on tabloid headlines are exploiting their naive ignorance of what they are copying; but should this innocence be played with? What does it really mean to take a sawed-off shotgun and saw it into particles? If you’re visiting the show, bring a controversial friend.

The later the work, the more politics and elegy.A great set of films including her drone footage Abandoned House of Commons, suddenly very small, haunted by newspapers that come to life as if trying to talk to absent MPs. Her research on Memorial Day poppy making noted a striking analogy between red paper tapes shunted and drilled in machines and huge mounds of waste matter thrown aside like fallen soldiers. Parker has a poetic eye for every detail that might matter.

Most impressive is the film portrait of a Palestinian Muslim who has been making the Crown of Thorns for 40 years for Christian pilgrims to Bethlehem. The film is nuanced and expansive, so one learns the process while thinking about the strange rituals that people imitate the crucifixion of Christ. The calloused hands handled the barbs with ease, but his heart did not harden. All he wants is a decent airport for better trade and peace in the Middle East.

The exhibition is so well arranged that the works are constantly communicating with each other – grid to grid, Rorschach to Rorschach, shed to shed. The missing buttons echo the faceless medals that only show the backs of political heads (Bush and Blair, made during the Iraq War).Flat silver returns with flat instruments Forever Canontheir dangling shadows drifted across the wall.

A sense of thought unfolding extends into Parker’s own writing on the wall. They act as an additional medium. Not only do they provide significant backstory to her approach — searing, squashing, stretching, shooting, spilling, dropping — but they add text as another art form.

The last job is Tate Britain Produced in 2022. It takes as much as possible her approach to words, objects and meanings. A greenhouse stands alone in a gloomy gallery, its overhead bulbs (think potting shed) coming and going to the rhythm of human anxious breathing. It has chalk all over its glass, made from Dover’s white cliff blocks. Nothing grows. All you can see are the church-style salvaged tiles in the Putin Commons, which line the floor. A little England, camped, closed, empty, cut off from Europe in one of Parker’s poems— island.