The Neptunes are being inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame next month alongside icons like Mariah Carey and the Isley Brothers. The duo, comprising Virginia Beach utility players Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, has had an unbelievable run. The Neptunes’ sound is at once identifiable and unpredictable, a left-field, minimalist approach to pop that trafficks in gorgeous if skeletal noise. Consider a song like Snoop Dogg’s “Drop It Like It’s Hot,” where wisps of steam and mouth-clicks provide rhythmic and melodic foundations, the SZA and Ty Dolla $ign single “Hit Different,” an arrangement of gossamer synth notes and delicate bass hits, or “Rockstar,” the lean, crunchy guitar jam from In Search Of …, the 2002 debut album from N.E.R.D., Williams and Hugo’s band with their childhood friend, Shay Haley. The sound is unorthodox but grounded in the friendship and unfussy musicality of two longtime collaborators unafraid to throw any idea at each other in service to making a great song. I rang Chad Hugo up last week to walk through the nearly 30-year history of his group, to trace the duo’s trajectory from high-school friends who jammed in Hugo’s parents’ basement to Grammy-winning hitmakers with fingerprints in multiple genres. I was floored by his humility as he discussed sessions with superstars and by the sense that he is just as content with hanging back doing his own thing as he is with workshopping hits.

I don’t get to hear from someone being inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame every day. How does it feel?

Oh man, it’s an honor. I’m excited about it. I feel grateful. I feel blessed having spent some time in the studio — time invested in learning music and applying it to recording, whatever Pharrell and I were recording back in the day, and seeing people being moved by it and affected by it emotionally and wanting to dance occasionally. It’s a good feeling to see people react to that and be a part of a community.

How did you get from high-school sax player to multi-instrumentalist super-producer?

Oh, it’s just I love music. I love communicating. My parents immigrated from the Philippines and moved to the United States. They had nine-to-five jobs. My dad was in the Navy, and my mother was a medical technologist. They purchased a piano for our home. I have an older brother and sister, and we used to spend time collecting records and listening to Top 40 on the weekends. I took piano lessons when I was a kid. I wasn’t really into it too much. You learn all the classics, which I’m appreciative of and grateful for now. It goes back, I guess, to buying records. That was, like, a thing that my family did. We used to go to Roses, a department store, and pick up records.

What were the records that turned you onto music in those days?

I remember bringing Joan Jett and Michael Jackson records to school in second grade and just dancing. Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” was awesome.

Why did you call your group the Neptunes?

For a while, we were in the studio in the garage at my mom and dad’s house. There was a four-track that I recorded on. Pharrell came up with the name. There was the local Neptune Festival, the planet Neptune, and king Neptune from Greek mythology. It encompassed everything from underwater to outer space. It sounded like something that wasn’t strictly hip-hop. It was out of the box.

You met Teddy Riley in the ’90s, and he put you to work on R&B records, but then in ’98, you get to produce Mase and Puff. How did that first rap hit, “Lookin’ at Me” from Harlem World, come about?

Pharrell and I recorded at Future Records, the studio in Virginia Beach. It was kind of a slower hip-hop type of groove. I sampled some drums from this record that my friend Bink gave me at the time — the “Funky Drummer” break. A lot of the sounds that were used in that record were chopped up from there. I had it in the ASR-10. We submitted it to Puff. They were really feeling it. I think we went to Quad Studios. It was awesome, man. I’m showing my age right now, but I grew up in the Roxanne era. One of my first hip-hop records was The Showstopper. A lot of the sounds that we used were not conventional. We were using stock sounds on the keyboard, which might’ve been out of the ordinary at the time. It was a matter of getting together with people in the record industry, and engineers, the people who make the record hot, and the A&R system back in the day. We would take trips to New York, fly out, and pitch these songs to A&Rs. We came up with hooks and rhythms and some songs there. I’ve just been blessed to be a part of the scene.

That classic Neptunes synth sound — I’m thinking of the beat for N.O.R.E.’s “Superthug” — was it a clavichord, or was it a guitar, or was it a synth and plug-in situation?

On “Superthug,” we utilized the clavichord, a clavinet, we call it. It’s a sound that was sampled from a Hohner Clavinet D6. If people don’t know what that is, it’s the keyboard sound in “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder. Not having access to an electric guitar at the time, we utilized that to get the idea out. Pharrell started playing it. We made the beat with drums from the breakbeat record that I sampled and chopped up. Tammy Lucas sang the hook. We were trying to reach all the demographics. The hook borrowed from “Heart of Glass.” The intro was a helicopter propeller, like how they found Manuel Noriega. To this day, no one’s heard anything like that. I know the Filipino American community is amped up when DJs play it at clubs and parties. It was different.

Talk about putting on for Filipino Americans in hip-hop.

As a community, we love music. Nat King Cole sang a song back in the ’60s that’s called “Dahil Sa Yo.” Our roots are just everywhere. Filipinos are everywhere.

I didn’t realize you played sax on Jay-Z’s “City Is Mine” off In My Lifetime, Vol. 1. I know there’s an incredible connection between Jay and the Neptunes, but I didn’t know it went back that far.

I was in the studio when Teddy was recording with Jay-Z at the time. He had a few records. I remember hearing “Who You Wit.” Jay was recording “City Is Mine” with Teddy, and Teddy invited me to play sax. That was a good experience.

In 1999, you connected with Clipse and recorded an album called Exclusive Audio Footage. Was that the first album that you produced for an artist from start to finish?

Yeah, Exclusive Audio Footage.

What was the story with the album not coming out?

There were lots of dope songs on there. I don’t know why it didn’t come out. I thought there were some good moments and some definitely out-of-the-box thinking there.

An album you worked on that did come out in 1999 was Kelis’s first album, Kaleidoscope. Recently, she has said she didn’t feel like the splits in that situation were fair. I’m curious what your response is.

I heard about her sentiment toward that. I mean, I don’t handle that. I usually hire business folks to help out with that kind of stuff. We made some cool records back then with Kelis. She was definitely eclectic and artsy, and she was nice. We recorded that album at a beach house in Virginia Beach, in Sandbridge, with the thought of it hitting the clubs and suburbs. That’s always the core: clubs and suburbs. It’d be great to connect with her again somewhere down the line.

In the early 2000s, at the peak of the TRL years, rock fans, pop fans, and rap fans were all kind of jostling for dominance. The Neptunes had rock records, Limp Bizkit remixes, and N.E.R.D. songs like “Rockstar.” You had NSYNC’s “Girlfriend” and Britney Spears’s “I’m a Slave 4 U.” You had hip-hop locked down. How you were able to stay that slippery?

I was always fascinated with DJ-ing and disc jockeys and being able to speak the language of music and get people together. Any way we can do that is my personal aim. Our aim was just to reach different audiences because music is supposed to bring people together, not separate them. We just wanted to get out there, share music, and have our records heard on the radio.

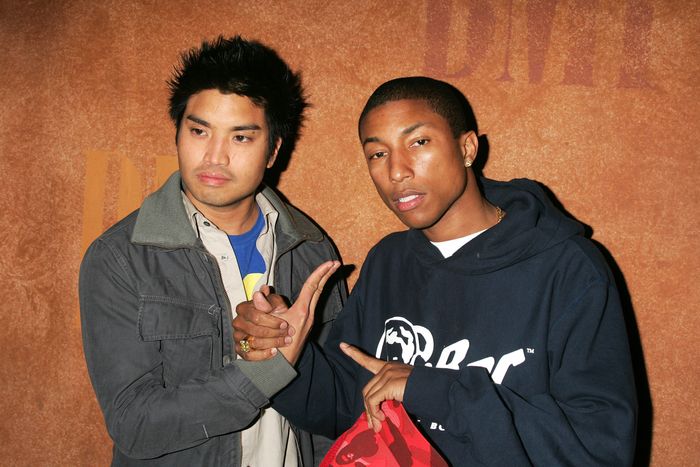

N.E.R.D. performing in the early 2000s.

Photo: Scott Gries/Getty Images

The 20th anniversary of the first N.E.R.D. album, In Search Of …, is coming up next month, and I’ve always wondered why there are two versions, the electronic version and the rock one that followed.

We were aiming to have a live feel and use our buddies, Spymob, the band from Minnesota. We enjoyed the music they were recording for us. I’d pitched them to a label and had them signed. Those guys were nice. Brent and Christian and Eric and John on the vocals. They kind of reminded us of a modern-day Steely Dan. They were dope. We wanted to record new sounds and get them played on rock radio. We didn’t think hip-hop radio as a format would be catered to with those kinds of all-over sounds. The sounds were eclectic, and they were different. There were a lot of changes. It wasn’t just a loop. I mean, it was loop-based … but we didn’t think that people would like it. We were just trying different things, just trying to find the right words to say.

In the early aughts, the Neptunes started a label, Star Trak Entertainment. You had an incredible roster, but a few years later, it sort of tapered off? Was there a story there?

I’ve always been proud of the Star Trak affiliation. Star Trak has been my heart and soul. When Pharrell came up with the idea for Star Trak, we were fans of the Star Trek show. We used to watch that as kids, the ’60s version. I couldn’t tell you what happened to the label. I think it’ll live on how it has. I was responsible for final mixdowns and studio work on a lot of those records. I’m grateful to have been a part of it. I’m no longer involved with Star Trak right now, with the merch or the company that has been relaunched.

One of my favorite Star Trak artists is Kenna. You produced his first album, New Sacred Cow, and most of the second one, right?

Yeah. He recorded a second album also, Make Sure You See My Face.

I thought it was a big deal that you were stepping out and producing that on your own. I never understood why he didn’t blow up in the way I expected. It seemed like all the stars aligned. I wonder if it had an effect on your thought process as far as endeavors outside of the N.E.R.D. and Neptunes banners.

At the time, Kenna and I weren’t really concerned about getting out there in the forefront. We just wanted to make a project. The first album was based on a lot of spiritual ideas. It was a tribute to his mom. It was really experimental, the way I chopped it up, the drum sounds. I think there was conflict as far as Kenna’s motive for making it. The industry wanted him to go out there and be seen, like, Look at me, I’m singing these songs, like a rock star. I think there was creative conflict.

What’s your process when you’re producing an artist? Are you intentional about it, or are you just kind of getting together and seeing what happens?

There are different ways of producing music. It’s just being prepared for however an artist wants to approach it. You always try to embrace the technology that comes out, the companies releasing software and different programs, different recording platforms. There’s this new thing called Audigo. It’s a portable microphone that syncs with your phone. There are all these new ways that may be worthwhile to look into. It’s just a matter of being prepared to go about making a song. You just have to be in agreement with people. Sometimes you can make it improvised and impromptu. Some of the best songs made are never recorded. There are jam sessions. Karaoke moments can have magic.

Between you and Pharrell, is there a take-charge person, or does it switch off, like how in Wu-Tang Clan sometimes one guy carries the record and sometimes it’s someone else?

I kinda always assumed the recording-in-the-studio duties. I sing songs at home, but I was never, like, a recording vocalist. Pharrell let me know, “However you want to be a part of it, we’ll go to the Grammys.” I was grateful for being available to help in any way I can. There are times when I sang background on some of the N.E.R.D. records and some of the Neptunes records that I’m not getting credit for or even worried about getting credit for. I was just trying to make the song sound dope and hit hard at clubs and have people moving to it in a certain way.

You’re willing to take the backseat in order to let a song go where it needs to go, and I feel like there are people who have started to question your impact. I’m curious if that’s something that’s on your radar, or if that’s something that even matters to you.

I’m a big fan of the OTHERtone series. One that was cool was the Internet. They showed up, I think it was a couple years ago, and they said that they were not going to stay around for a while. They had records to make, and they wanted to break off and do their own thing, and that was a good thing. Another group that said that was Brockhampton. They kind of did their thing, and now they’re going solo. It’s interesting that they came up with a plan, you know what I mean? They came up with a timeline and just said, “This is how we’re going to live our lives.” When Pharrell and I started making records, and we had a record label, and did all these things with N.E.R.D., we just kind of went with the flow. The whole thing has just been one mixtape. Our life has been one mixtape. With the knowledge and technology available, there’s a good way to plan stuff out and be content with following through and achieving that plan and celebrating the success of achieving that goal that was in mind. I don’t know if that answers the question.

What I’m hearing is that you’re content with the way things turned out, in spite of the way that other people might see things. I mean, it sounds like one guy was the vocalist, and so he naturally was going to be a lot more places, and maybe people get ideas off of that.

Absolutely. Yeah. Pharrell was definitely the vocalist and the spokesperson, the lyricist, and he wrote the hooks.

Are there records you regret not playing on that you could have been a part of?

I was there when I needed to be there. I did my thing and was glad to be a part of it. I helped the best way I could at any time. I was there and did what was needed from me and did what was necessary without compromising any creative integrity.

Photo: Jeffrey Mayer/WireImage

It’s commendable, over a span of decades, to be able to say that. The Neptunes reunited with Justin Timberlake in 2018 for Man of the Woods, but the album received a negative response. But I felt like those beats were doing something smart. They found this strange common ground between country and R&B. It was interesting stuff. How’d you feel about the reaction to that one?

I mean, it would be nice to go back and, like — sometimes records are given a different chance, a second chance, as far as being remastered. People should start reworking things more often. I like that the Beatles will sell an album full of studio sessions that shows bloopers and outtakes.

There’s been some speculation about who actually wrote the McDonald’s “I’m Lovin’ It” song. What do you remember?

Pusha T says that he wrote it, right? I didn’t know that. I remember Justin singing the hook. I think it was Steve Stoute who approached the Neptunes and our management to make the remix, so we recorded it in our studio here in Virginia Beach. Justin sang the song. It’s a pretty cool song.

I was looking over the credits for Pusha T’s album It’s Almost Dry, and I didn’t see you in there?

I was involved in that record, to be honest with you. We’re trying to work that out.

Was there a mix-up with the credits?

I guess you could call it that.

Would you call it something else?

We made some tunes. There were some good vibes there. We recorded it in Florida at a boathouse studio. I played some keys here and there. I was present.

It sounded like primo 2000s Neptunes to me. Thanks for clearing that up. What are you working on these days? Are you still in the studio all the time?

I’m in the studio all the time, yeah. Right now, I’m working on production with this artist named the Blossom. She’s, like, a pop-rock alt artist. I’m working with Dan the Automator on a Jo Koy comedy called Easter Sunday. I have a tune out with Denzel Curry. There are different things that I haven’t put out yet.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Virginia beat-maker Roosevelt “Bink” Harrell III produced classics like Blackstreet’s “Don’t Leave Me,” Jay-Z’s “All I Need” and “1-900-Hustler,” Rick Ross’s “Santorini Greece,” Drake’s “Jodeci Freestyle,” and Ye’s “Devil in a New Dress.”

OTHERtone with Pharrell, Scott, and Fam-Lay is an Apple Music podcast where P discusses culture with music supervisor Scott Vener, Clipse associate Fam-Lay, and entertainment-industry guests from Druski to Gary Vee.