Forty-three kites with 43 black and white faces hung from Queen Sofia’s ceiling, each one silently calling for answers, remembrance and justice.

Nearby, T-shirts and posters call for equality, a woodland placard commemorates those detained, missing and killed by Uruguay’s military dictatorship, while symbols of Peru’s struggle for independence have undergone a queer pop-art makeover.

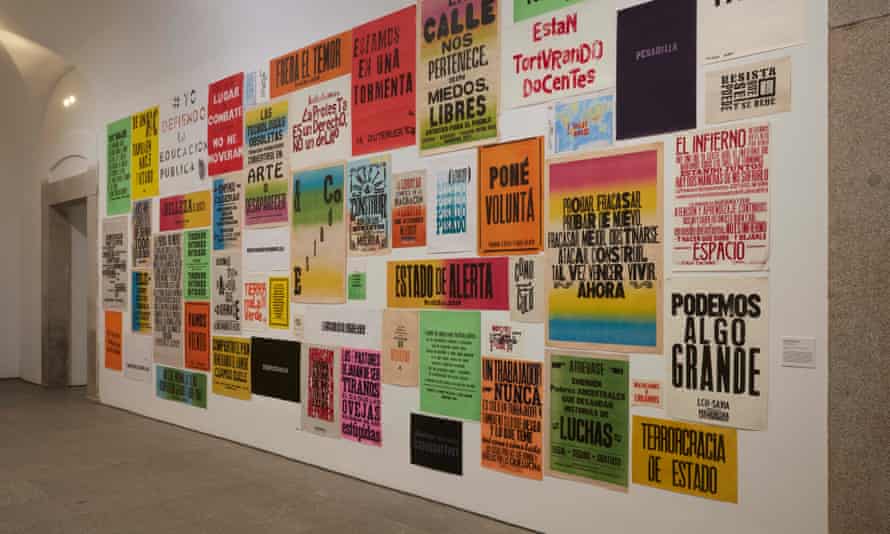

The latest exhibition at the Madrid gallery explores how graphic art has been used to fight political repression and demand social justice in Latin America and beyond, whether on walls, posters, prints, flyers or fabrics over the past 50 years.

Call Graphical turn: like ivy on the wallwhich hops around some key sociopolitical moments in recent regional history, examining the reactions they evoked on the streets and beyond.

The show is based on research by Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Southern Conceptualism Network), which has been studying for years how street art can be used as a tool of creative resistance in Latin America.

While some exhibits are angry at dictators, torturers and foreign interference – a poster titled Stop Yankee Attacks Nicaragua An American eagle is shown swooping down on an armed crowd – others gain strength from silence and pain.

The whole room is handed over 43 students, teachers missing In Mexico in 2014, its fate sparked fierce protests.

In addition to posters and kites featuring the faces of the missing, there are panels embroidered with messages, some sad – “They sowed the seeds of tomorrow’s struggles”, “Your future students are waiting for you in the mountains and they can learn from them ‘s first letter” – somewhat angry: “they kept them alive, we want them alive” and “don’t forgive, don’t forget”.

Another room uses drawings, posters and photos to document Nicaragua’s Sandinista revolution — and charts President Daniel Ortega falls into despotism.

“These posters were designed to be posted on the street,” said Ana Longoni, one of the coordinators of the Southern Conceptualist Network.

“But it’s also important to us that while these materials, techniques and tools can be used in public spaces, when you put them in museums, they can also be a very powerful indicator of what’s going on in Latin America. soundboard, in the rest of the world.”

Sign up for the first edition, our free daily newsletter – every weekday at 7am BST

According to Manuel Borja-Villel, director of Reina Sofía, the project aims to see political graphic art as something that “lives, mutates and creates a dialogue between past and future”.

In the exhibition catalog, he wrote: “Like ivy, graphic art grows on walls no longer made of stone, and bursts again and again. It takes on new forms – often containing echoes of its predecessors — but it never lost its ability to ask us questions.”

The exhibition also explores how marginalized and abused people use graphic art to fight back.

Poster by Peruvian artist Natalia Iguiñiz titled My body is not a battlefield, shows the silhouette of an Aboriginal woman against a camouflaged backdrop and serves as a reminder of the thousands of women and girls who were raped during the country’s war with terrorist groups in the 1980s and early 1990s. Thousands of Peruvian women – many of them poor, illiterate and indigenous – also forced to sterilize Under the authoritarian government of Alberto Fujimori in the late 1990s.

Another Peruvian piece, featured in the show’s secret area, reflects how the LGBT community in Latin America used graphic art to connect and organize in the 70s and 80s.

Javier Vargas Sotomayor’s 2006 “Fake Tupamaros” Eight gay and trans men murdered They were killed in 1989 by terrorists from the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement in northern Peru. In it, the artist takes a portrait of the 18th-century Peruvian independence leader Tupac Amaru II — from whom the terrorist takes its name — and subverts him by comparing his features with Frida Kahlo, Farah Features of famous women such as Fawcett and Marilyn Monroe merged into a masculine, militarized image.

Sol Henaro, another of the exhibit’s investigators, likes to think of the project as a “series of detonators,” rather than exhaustive, encyclopedic, or linear.

“There is a poem by the Paraguayan poet Susy Delgado called Curuguaty-Ayotzinapa that speaks of two very tragic moments in the contemporary era,” she said. “The last point reads, ‘The same tragic story / In the deaf notebook of time / Repeated a thousand times’. We think this exhibition is about being the deaf notebook of time.”