FNew artist’s connection to a single painting is as strong as Edvard Munch’s that scream. Even before its inexhaustible memory became apparent, it was a fixture in pop culture and art history.But Munch was always more than his most famous work, and New exhibition at Courtauld Gallery, London Provides a rare opportunity to trace his wider career.

The exhibition is part of the collection of Norwegian industrialist Rasmus Meyer, who discovered Munch’s work in the early 20th century and soon became an avid supporter and collector, continuing to buy paintings directly from Munch’s studio at the time The paint is almost still wet, as the saying goes.This is his first collection, in Cod Art Museum In Bergen, it has been exhibited together outside Scandinavia. It worked from the 1880s, when Munch was a rising star in Norwegian art, until the “Golden Decades” of the 1890s, when he developed his own unique style and created what is known as his work. frieze of life series, including various iterations of The Scream – and into the 20th century.

Subscribe to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly picks.

“Norway didn’t really start to be an independent country until the end of the 19th century,” explains Courtauld curator Barnaby Wright, “while Meyer wanted to collect Norwegian art to express their culture and identity.” Not that Munch His work was generally appreciated in 19th century Norway. While he was gaining international recognition, the debate between conservative and avant-garde views unfolded in a manner similar to the French Impressionists of the 1870s.

The layout of Courtauld, passing their collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art on the way to the exhibition space, was perfect for this exhibition. Munch was fascinated by Impressionism’s exploration of the effects of light and the new techniques for capturing them, but the lessons he learned were then used for his own purposes. Rather than follow Monet in taking his canvases outdoors to nature, Munch was more interested in painting from memory and imagination, using light in a more expressive and symbolic way.

By the 1890s he had developed this style of painting, using richer, more moody colours to create an atmosphere of anxiety, with figures and landscapes increasingly reflecting each other. He named these explorations “The Fascia of Life,” and “his goal was to encompass the deepest human emotions and experiences,” Wright explained. “Frequently draws inspiration from his own childhood memories; loss of a loved one; painful relationships with women. What makes these pictures enduring is the complexity and variety of emotions and emotions he evokes. No matter how wonderful The Scream may be , it is just one example of Munch’s extraordinary work. This collection shows why many of his pictures are still so powerful to us.”

“Sickness, Death, and Unstable Anxiety”: Four Highlights of the Exhibition

Karl Johan Street by night (1892, main image)

Light plays a crucial role in all of Munch’s work, and here he captures the creative possibilities of strange moonlight mixed with gaslight. Karl Johans Street Night is an important frieze painting, and Munch first used those skeleton faces looming from the canvas, which he repeated in his Scream paintings. This is the original image of the now famous visual device.

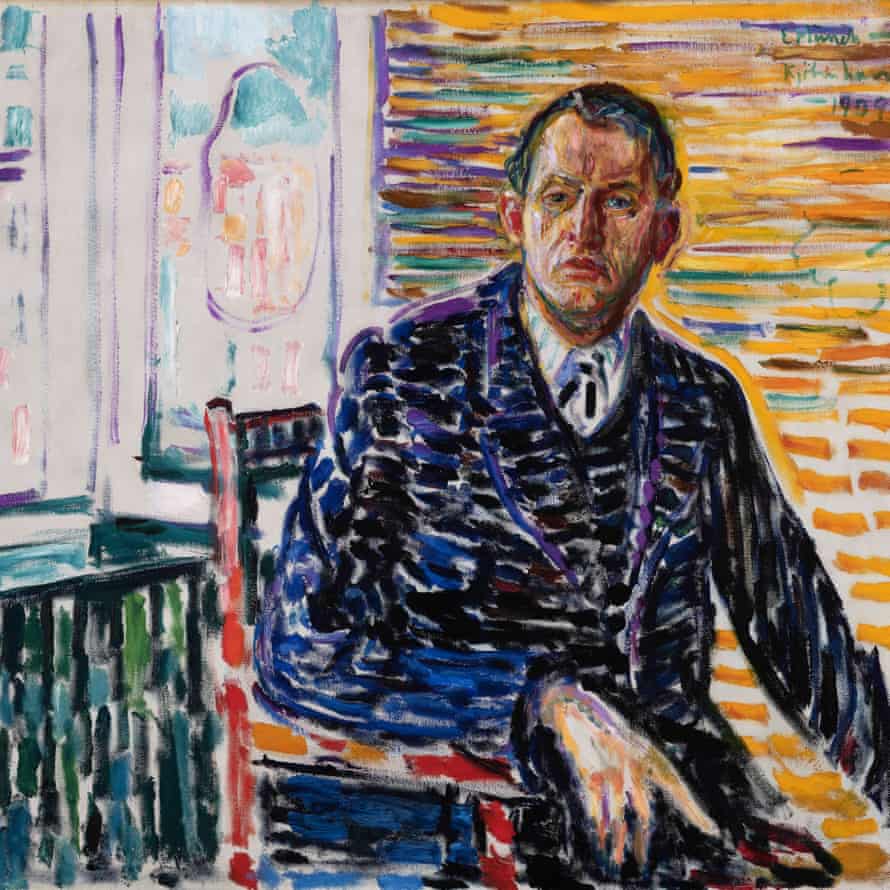

Self-portrait at the Clinic (1909)

When Munch had a nervous breakdown, he sought treatment at a clinic in Copenhagen. His life was stressful. When Munch was a child, his father was very religious, and an atmosphere of sickness and death hung over the family. It persisted for the rest of Munch’s life, and it was this sense of precarious anxiety that infused his art. This particular work bears an interesting resemblance to Van Gogh’s self-portrait after a serious psychic event depicting a man and artist trying to reconstruct himself.

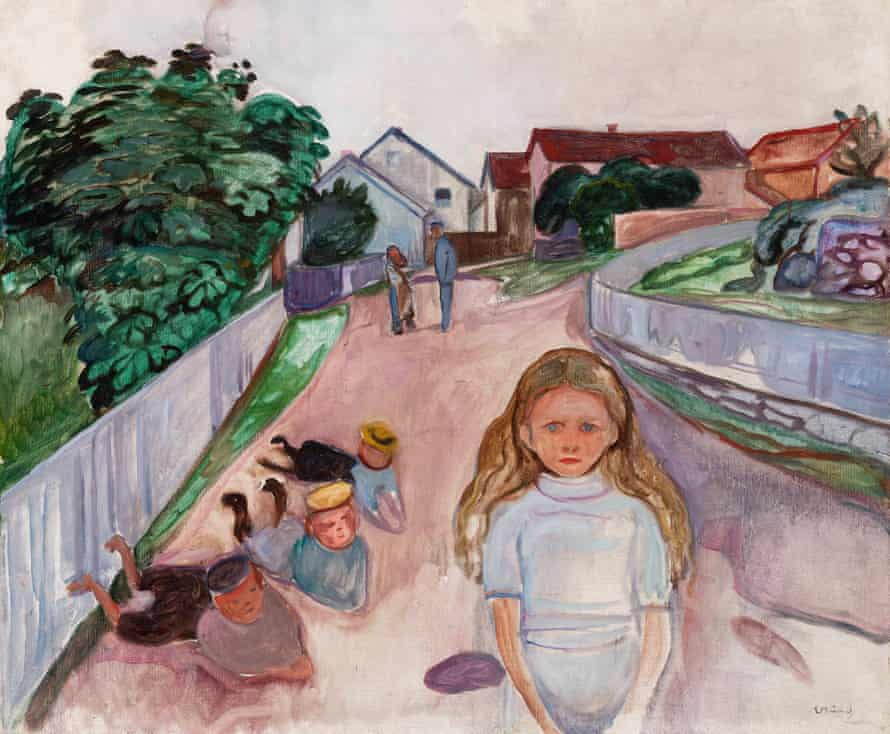

Children playing in the streets of Åsgårdstrand (1901-03)

Many of Munch’s summers are spent in the small coastal fishing village of Åsgårdstrand. Here, he turns seemingly mundane daily activities into something more profound. Are the boys mocking the young girl and making her an object of desire, or are they just playing around? Equally mysterious, is she on the verge of puberty asking for help or confronting them?

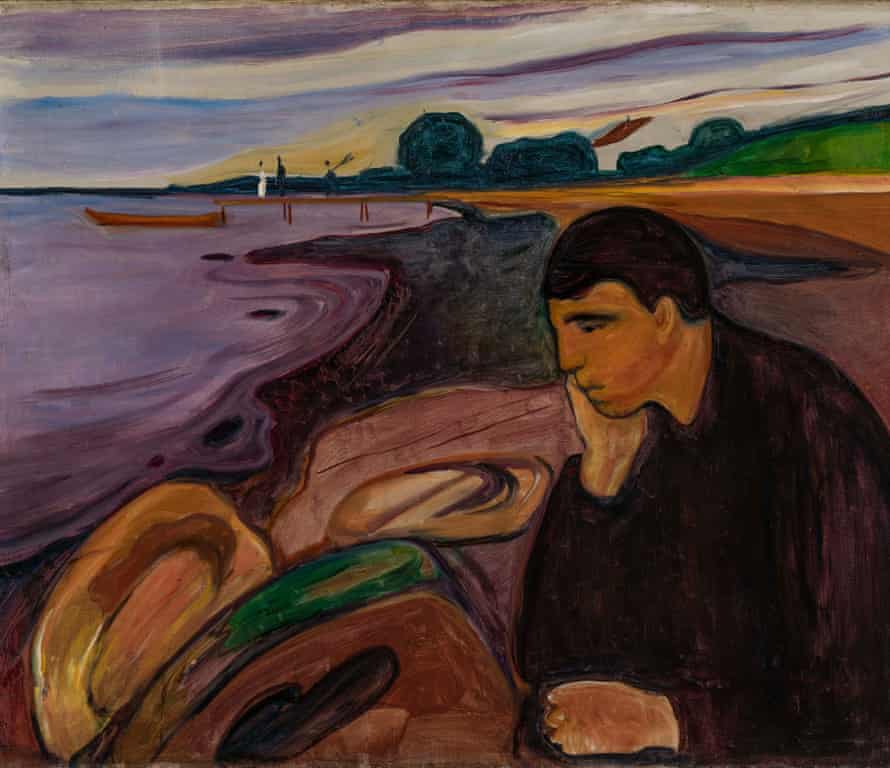

Melancholy (1894–96)

The idea that emotions are at their most extreme when people are on the edge between shore and water is a fertile one for Munch. Here, it reflects the state of mind of the central figure, lost in his own tragic thoughts, also isolated from the two background figures on the pier. This is the first time Munch has adopted this new deeply moody and symbolic approach.

Edvard Munch: Bergen’s Masterpiece Now in the Courtauld Gallery, London, courtesy of Friday to September 4th.