DDespite ultra-low emission regulations, a flood of diesel vans is still blocking London’s Euston Road, historically one of the most polluted streets in the country.It is a suitable location for an awareness-raising exhibition Wellcome Seriesnot exactly a breath of fresh air, but an exhilarating, exhilarating and potentially rejuvenating quest into a surprisingly long history of fighting for the breath.

up in the air A mix of works by contemporary artists, including Dean Tacita, Dryden Goodwin and David Ricardand fascinating archival material revealing the early battles for clean air from the Fumifugium, or, the inconveniences of Aer and Smoak in London, a prescient 1661 pamphlet by John Evelyn that One of the earliest known writings, imploring the authorities to take action against pollution.

Air may be the most elusive and challenging of the elements that give an art form, but it’s working. Goodwin drew attention to London’s toxic air in 2012 when sketches of his 5-year-old son’s breathing were projected onto St Thomas’ Hospital, opposite the Houses of Parliament.He returned to the topic a decade later, attracting anti-pollution campaigners from London near his home in Lewisham, London, including Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, whose nine-year-old daughter Ella fell ill in 2013 Suffering from deadly asthma, becomes UK’s first person to suffer from air pollution listed as her cause of death during her interrogation.

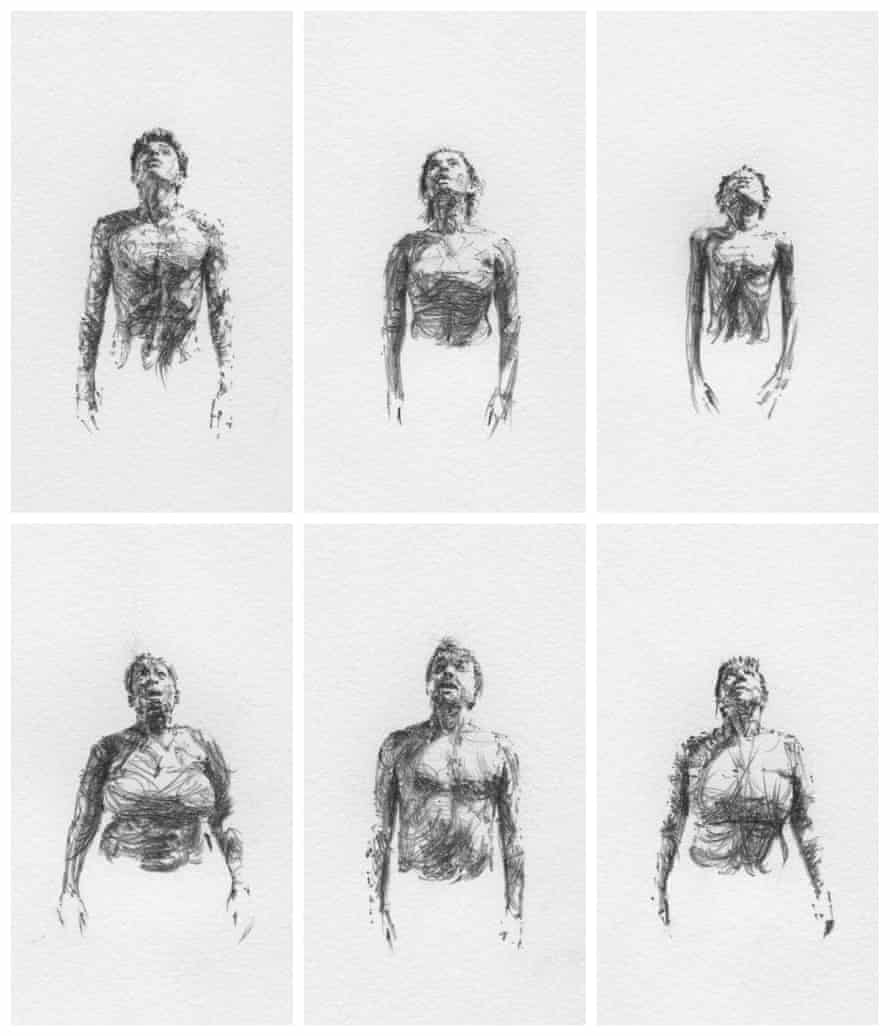

Six locals – including Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, Anjali Raman-Middleton’s clean air campaigners choked upand Goodwin’s own son Heath – before Goodwin sketched each of the multiple frames in miniature with a 0.5mm mechanical pencil. The vivid little sketches show every activist drawn from the waist up, wearing as little as possible so you can see their skin taut over their ribs which somehow conveys the fragility of breathing and radical resistance.

Goodwin is still Breathe: 2022 This will also appear on billboards, bus stops and parliament buildings in Lewisham, culminating in a large public projection of the full animation of over 1,000 drawings in November in partnership with arts and science charity invisible dust. The project grew out of a deep personal fear of his five-year-old son. “Drawing my son is about my sense of responsibility to him,” he said. “We choose to put our children in this environment.” But he is acutely aware that while he may have chosen to live in Lewisham, others have not. “We don’t all breathe the same air. I live not far from where Ella was so badly affected. I live a few roads back, but it’s very different.” Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s words will appear in Below one of the pictures: “Do we all breathe the same air?”

After a “provocation” projected across parliament, Goodwin was invited to a panel discussion on air pollution hosted by the Environmental Audit Committee. “So I went and it was fantastic, I thought, something happened here. And then MP Joan Worley, who has done a great job on this issue, said ‘You have to write to your MP and express these things”, I thought, but we’re in the House of Commons! We have to get on with these things!”

The government is currently proposing air quality target Small particle pollution in England is allowed to be double the limit recommended by the World Health Organization, a target that won’t be reached until 2040. Is Goodwin frustrated by the lack of progress over the past decade? “What happened during that time was disturbing, it was actually scary. We knew that was the way to go,” he said. One of the biggest positive changes, he believes, was the tragic death of Ella in his borough, which inspired a new generation of young activists. “The scale of air pollution is overwhelming, but it is only through local that it is possible to gradually deal with the global scale. It is very important that the people I paint this time are active and agents of change.”

Visitors to the Wellcome exhibit will see Tacita Dean’s delightful, vertiginous short film about collecting air in a hot air balloon, as well as a stack of concrete blocks assembled by David Rickard. A Roomful of Air measures the amount of air in the gallery, calculates altitude, humidity and temperature – all of which affect its weight – and expresses this staggering weight in concrete – over 1,400kg in this particular room.

“There’s literally tons of stress on our bodies,” says Rickard, a lovely New Zealander living in London, who is enthusiastic about the idea of clever collaborations with scientists. “In the ocean, there are fish that live in the midnight zone; we live in the midnight zone of the atmosphere — it’s under enormous pressure.”

Rickard, like Goodwin, has been creating art out of thin air for over a decade, and since then exhaust, he sat in a mask with a valve for 24 hours and collected all the air he breathed with a foil balloon. This eerily beautiful and exhausting performance art often results in sculptures of 98 to 102 Rickard’s breathing balloons rising above his contemplative image.

Instead of having to complete the marathon for In the Air, Rickard showcases international airspace, which brings to life Dean’s film idea of collecting air from the 27 original signatories to the 1919 Paris Convention.

“We’re talking about ‘our’ airspace in a national sense—obviously, it’s a completely unrelated way of thinking from an atmospheric and environmental standpoint,” said Rickard, who was inspired by caesar’s last breath, a book by Sam Kean that reveals how the air we breathe today circulates around the hemisphere every two weeks, with each breath we take in a molecule that Caesar would have on his last breath Breathe into this molecule. “That’s when we started to realize that the concept of pollution and the changes we made to the atmosphere wasn’t going to go away,” Ricard said. “For thousands of years to come, people will be breathing the pollution we create now.”

Rickard found collaborators in every one of 27 countries, from Belgium to Uruguay, who collected the air in special plastic bags and sent him boxes of air. “It was very inspiring that people would come to ships with weird things like ‘Can you collect some air?'” Eventually, the air was obtained, which Rickard released into a glass blower (a Dying Art or Science) in elegant glass tubes. Rickard said) at the University of Leicester’s School of Chemistry.

Rickard’s work may not be overtly controversial, but he is passionate about raising our awareness of the air we breathe by showing the materiality of air. metallurgythe duo of Helena Hunt and Mark Peter Wright, who presented a new video installation, Air Forms, in collaboration with production studio artXR.

In an immersive panorama film developed for the exhibition, visitors use VR headsets to encounter giant particles of pollution—and they talk to them about this “toxic ecology.”

“In popular culture, there is a growing recognition that air is economic and geopolitical, and influenced by industry and pollution,” Hunter said. “For us, it’s very much about the animation itself and how the sound of the particles is communicated to the audience – translating scientific knowledge into something perceptible, physical or more poetic.”

The people in Goodwin’s breath are small and fragile, while the fly ash particles are magnified to be larger than people. “Fly ash particles are produced by coal-fired power plants, and fly ash is the star of the show,” Wright said. “It will address you as a gallery visitor. We really wanted to create a slow encounter to somehow move and think about these toxic realities that underpin life but we are seldom aware of. We don’t want it to be controversial Yes, but it’s a very serious topic with a lot of different culpability and implications for who has the right to breathe.”

“We wanted to create a contemplative space where you can really feel this toxic intimacy and think critically about it,” Hunter said. “The soundtrack creates a feeling of mourning and meditation — not in a very focused way, but in a very focused way.”

Goodwin hopes that the exhibition’s aviation art will not only focus on ideas, but also contribute to political action. He believes that the city council and the London Mayor’s Office are listening to local activists highlighted in Breathe:2022, but want change at a higher level. “These are very important, Rosamond said. [artistic] Things happen, awareness rises, the unseen becomes visible, but action must also happen. There needs to be more bike lanes and pollution limits must be respected. Politicians can’t just think “we’ve shown some pictures”. I’m very aware of art cleaning, but we have to do something good, and that’s what I do. “