Scooters, bikes and motorbikes continue to make their way through the endless gridlock in Mexico City. Drivers of these two-wheeled vehicles often carry large boxes emblazoned with the brand names of last-mile delivery apps, all of which deliver food and other goods to local residents. But now, Rappi users can order health services directly through the platform’s app.

Wearing a medical gown and helmet, a nurse works on Rappi’s home delivery shift – she and Rest of the world On the condition of anonymity to protect his work — he said he was recruited in early 2022 by a private medical lab working with the app. He usually works eight-hour shifts from 7am to 3pm and gets around on a lab-provided motorcycle, which also pays for his fuel. He is particularly satisfied with his new job.

“I’m a lot faster on my motorcycle…so my shifts usually end on time,” he told Rest of the world. “Sometimes I go to the park or have lunch between dates.”

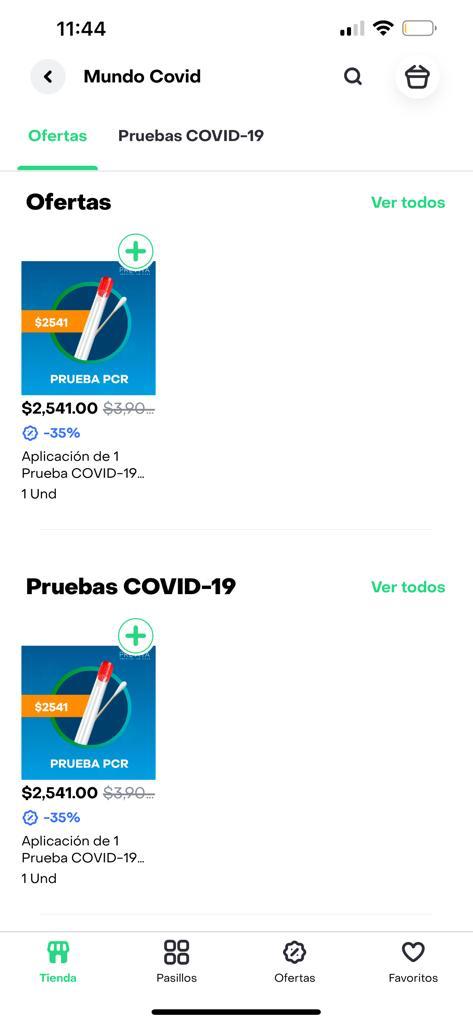

Rappi is the ubiquitous last-mile delivery platform founded in Colombia in 2015 that allows users in Mexico City and Bogota to order and book blood draws for HPV for clinical lab tests, pregnancy, STI and Covid-19 tests, and vaccinations , Herpes and Pneumococcus are delivered and applied in their own home. Beginning with Covid-19 testing in 2020, Rappi now acts as an intermediary for six health care providers in Mexico City, whose staff apply the test or vaccine and then process the results.

Rappi executives and one of the healthcare providers they work with told Rest of the world The pandemic presents an opportunity for partnership to be mutually beneficial. But healthcare workers also won. For nurses who asked to remain anonymous, delivery jobs meant the chance to get a full-time job. Viviana López, also a trained nurse, has been with Rappi’s partner supplier, Previta, for seven years and oversees its laboratory department, which is an opportunity for her to do better at her job. “It’s very rewarding for healthcare workers like us to be closer to patients at times like this.”

Rappi’s model of delivering health services through partnerships after screwing up most of its own company’s health care policies throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.The first stumbling block for self-proclaimed super apps as it tries to beef up its delivery service Serving millions of people locked down, and when it infamously tried to dispense small amounts of Covid-19 vaccine to workers based on their delivery performance. Rappi Mexico’s new vertical manager, Gloria Ruiz, told us that the company backed down quickly, but it never lost sight of the opportunities offered by “health care, home testing and vaccinations.” Rest of the world.

After users order health services on the Rappi app, the lab takes care of the rest. The healthcare provider was notified and one of the employees was dispatched to the client’s home.Unlike the last mile delivery app’s trademark oversized orange backpack made by the typical Rapidendros, healthy Workers are outfitted with regular people full of tourniquets, needles, gauze and other equipment. Staff rushed back to the lab before their next appointment, and many results were sent to users within 24 hours via WhatsApp or email, not through the Rappi app itself.

Both López and Anonymous Nurse became delivery men thanks to their employer’s partnership with Rappi, but were far from gig jobs.

“You become a gig worker,” said Miguel Díaz Santana, digital worker coordinator for grassroots workers’ rights and civic advocacy group, slugTell the rest of the world, “When you don’t have a steady salary, benefits or employment rights.”

But at least two of the nurses interviewed were fully employed by the company that supplies Rappi with health workers. Morgan Guerra, co-founder, CEO and head of medical affairs at Previta, the lab that employs López, said that while his company doesn’t employ all medical staff full-time, all employees who provide at-home services do so through facelifts. This is in stark contrast to the typical “last mile” app delivery worker, who works long hours as a third-party contractor on a pay-per-work basis without any kind of social benefits.

“In the gig worker-employer relationship, the job doesn’t disappear — it’s the employer that disappears as the person who has to protect these labor rights,” Diaz Santana said.

While last-mile delivery apps like Rappi have been criticized for the working conditions of mobile couriers during the pandemic, Ingrid Ortiz, a lawyer and digital health expert at Mexico City law firm Olivares, said Mexico’s legislation related to labor and health Not as flexible as consumer product delivery. This means that the rights of health workers are universally guaranteed.

For healthcare providers, working with Rappi is a “natural fit,” Guerra said. In the early days of the pandemic, his company was forced to switch from providing healthcare to people through employers to providing healthcare directly to individual clients through their own company. E-commerce platform.

“Everyone became an expert on rapid testing,” Guerra told the rest of the world, Refers to the numerous small testing companies that have sprung up during the pandemic. “We realized we had to keep pace, so we partnered with Rappi to provide B2C services,” supporting their own internal platform.

However, Díaz Santana, an advocate for digital workers, expressed concern about the on-demand model adopted by more industries and what it means for deliverers. The danger is that the delivery model spearheaded by Rappi could become a weak link in the introduction of other practices that make the workforce temporary: “It is worrying that other industries adopt a precarious distribution platform model because they are not providing social safety and encouraging informal labor,” he said.

Although online healthcare has not been directly addressed in any specific legislation, lawyer Ortiz said, “under Mexican labor law, they are likely to have contracts with collaborating labs, which means defined hours of work and the need for labs. Sexuality complies with certain specific regulatory requirements.”

Ortiz does expect the practice of healthcare home delivery to grow. “Mexico is one of the most attractive markets in Latin America due to the size of the country, so sooner or later it will be the target of all players in the field,” she said.